Detroit

The summer of 1967 was a hot one. Racial tension was high in Northern cities like Detroit, as post World War II suburban flight had left black factory workers and their families cramped into dense public-housing tenements. Then on the evening of July 23rd, Detroit police raided an unlicensed after-hours nightclub on 12th street. The resulting riot was one of the most destructive in American history. It lasted five days, and resulted in Governor George Romney’s implementation of the Michigan National Guard to keep the peace.

The summer of 1967 was a hot one. Racial tension was high in Northern cities like Detroit, as post World War II suburban flight had left black factory workers and their families cramped into dense public-housing tenements. Then on the evening of July 23rd, Detroit police raided an unlicensed after-hours nightclub on 12th street. The resulting riot was one of the most destructive in American history. It lasted five days, and resulted in Governor George Romney’s implementation of the Michigan National Guard to keep the peace.

Focus on Algiers Motel

On the fiftieth anniversary of this unfortunate episode in U.S. history, director Kathryn Bigelow has recreated some of the events of that week in a gripping new thriller, “Detroit.” Bigelow’s film targets perhaps the most lamentable crisis of that week, the Algiers Motel Incident. Following a false report of sniper fire emanating from an upstairs window, Detroit police, state police, national guardsmen, and a security guard proceeded to denigrate and badly beat a group of black males and two white females over the course of the evening. Three black teenagers were killed. It is a story of a police force with a license to intimidate, humiliate, and (if deemed necessary) murder any African-American who doesn’t fully cooperate with white authority figures.

Poulter is brilliant

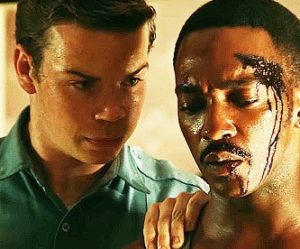

Will Poulter plays the leader of the city police detail called to the scene. Already having been reprimanded for shooting a black man in the back earlier in the week, Poulter’s character screams, pummels, and fully conquers the fragile psyches of the black men under his tutelage. His character is pure evil, and rivals Malcolm MacDowell’s Alex from “A Clockwork Orange” as one of the most horrific villains in motion picture history. His is a character you won’t forget. Poulter deserves an Oscar nomination for Best Actor.

Will Poulter plays the leader of the city police detail called to the scene. Already having been reprimanded for shooting a black man in the back earlier in the week, Poulter’s character screams, pummels, and fully conquers the fragile psyches of the black men under his tutelage. His character is pure evil, and rivals Malcolm MacDowell’s Alex from “A Clockwork Orange” as one of the most horrific villains in motion picture history. His is a character you won’t forget. Poulter deserves an Oscar nomination for Best Actor.

The Dramatics

In a little-known footnote to the Algiers incident, several of the black men involved are members of The Dramatics – a male vocal group trying to land a contract with Motown Records. Four years after the riot, the Dramatics burst onto the music scene, placing “Whatcha See is Whatcha Get” and “In the Rain” in the Billboard Top Ten over a six-month period. Following Algiers, one of the members quit the group in favor of a career as a choir director at a local Detroit congregation. His reasoning: As a black musician, he was unable to consciously make music for a white audience after the horror of Algiers.

In a little-known footnote to the Algiers incident, several of the black men involved are members of The Dramatics – a male vocal group trying to land a contract with Motown Records. Four years after the riot, the Dramatics burst onto the music scene, placing “Whatcha See is Whatcha Get” and “In the Rain” in the Billboard Top Ten over a six-month period. Following Algiers, one of the members quit the group in favor of a career as a choir director at a local Detroit congregation. His reasoning: As a black musician, he was unable to consciously make music for a white audience after the horror of Algiers.

Violent Revolution

In one of the most memorable early scenes, a white man asks a black man why their revolution need be so violent. The black man responds that White America’s revolution (that for freedom from Great Britain) was also brutal. “All that ‘Give me liberty or give me death’ – that wasn’t violent?” he inquires.

Parallel with today

The parallel between the 1967 Detroit riots and the white-on-black police murders of the past few years is striking, and none too thinly disguised by Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal. In fact, the Detroit police are perhaps unfairly singled out as the proverbial bad guys in the screenplay – even though historical accounts also implicate the state police and National Guard.

How far have we come?

On the one hand, we see how far racial relations have advanced during the past half century. Hearing newsmen (including the late Frank Reynolds) using the term “negroes” does seem archaic, if not downright derogatory. On the other hand, the similarities between Detroit and today’s police shootings (including the legal cover-up of “justifiable homicide”) depict just how far we still have to go to achieve a truly racially-blind society. What would it take to bring justice to the victims of white police brutality today? Might it take another Algiers? In the hope that it does not, Bigelow has put the 1967 episode (in all its revulsion and carnage) on the big screen for us to ponder.

Bigelow’s best picture

Although she won Best Picture and Best Director for 2008’s “The Hurt Locker,” I believe “Detroit” is actually her best film to date. Given the age of the incident and the fact that many of the principal players are no longer with us, some of the fine details of the 1967 riots had to be filled in with dramatic license by Boal. While purists may lament this fact, dramatically it works to Bigelow’s favor. In “Detroit,” the action begins while our popcorn is still warm. In much of her previous work, she became bogged down in detail – often to the detriment of the narrative.

Comparison to “Zero Dark Thirty”

In 2012, I wrote that the first hour of Bigelow’s “Zero Dark Thirty” could have been compressed into about ten minutes, and we would have understood that a lot of off-the-record negotiation was necessary to locate Osama bin Laden. The screenplay simply featured too much undercover arbitration before the action kicked in. I realize writers typically choose facts over poetic license, but I found much of it boring.

Masterful achievement

Not so here. “Detroit” grips viewers practically from the opening minutes. The archival and recreated footage of the first two days of the riot is compelling. Then, just when we think we’re in for a pseudo-documentary, Bigelow and Boal throw the Algiers incident into our faces point-blank. The result is an unforgettable motion picture experience. This is an important, relevant film, which should rear its head at Oscar time. It’s a masterful achievement.

Andy Ray’s reviews also appear on http://www.currentnightandday.com/

and he serves as a film historian for http://www.thefilmyap.com/